The last poet of the twentieth century: interview with Mariano Bàino

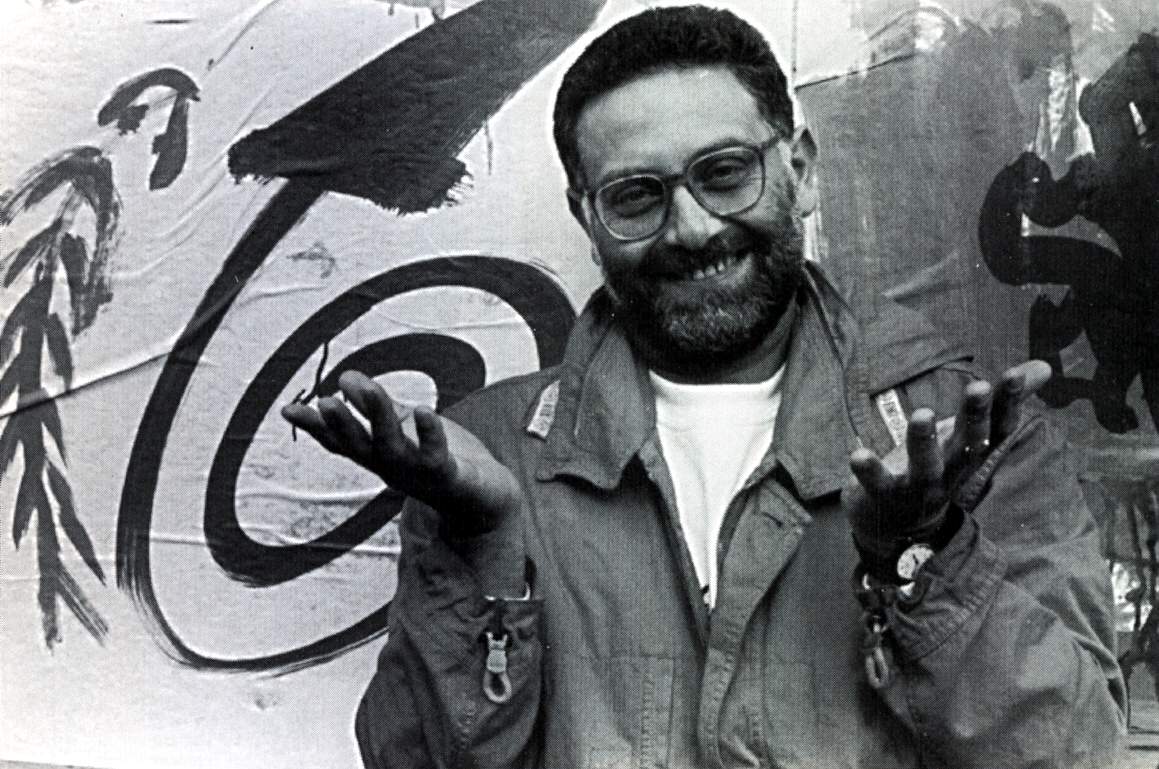

Mariano Bàino was born in Naples, in 1953. He is a founding member of the so called group 93 and the magazine Baldus. His poetry has inspired an important debate, indeed, the last major debate of the last century about poetry.

In this interview with Mariano we would recall his entire poetic experience, from the debut with Hyperbaric Chamber (1983) until the last sestets published on magazine in 2003.

– In 1963, the group ‘63 gathers up near by Palermo, in order to discuss around the new avant-garde.

In 1969 Adriano Spatola published the essay Towards the total poetry.

How these two events have affected your poetic formation?

I thought, at first, with Greenberg, an art split into vanguard and falsehood. Later I have also been fascinated by the modern classicism. I think there is such oscillation in my work. But the echoes of the discussion of the Group ’63 have definitely affected upon my poetic education. What a great laboratory those discussions of poets, writers, critics. So many ideas to think about! For example, the idea that into the language is included not only the liberation, but also the alienation; a way of feeling that welcomes disharmony; a relationship with reality supported by a renewed sensory sensitivity; the commitment as something that should not give prior to the poetry, but it must be done with the same act of writing poetry; the contradictory: stay inside the literature by aiming at an out of the literature; taking away from the existent; the idea, of Umberto Eco, that the artist has started to be more and more, when he prepares to compose, a novice in the void… And Adriano Spatola, with its hypothesis of the total poetry, offered me the chance to reflect on a experimentation that went beyond encoded genres of the literature and which involved every expressive field, intersecting the writing, the voice, the image, the action. An art moved on orality as on the visual representation, on the body as on the mutual crossing of languages.

The last poet of the twentieth century: interview with Mariano Bàino

Mariano Bàino was born in Naples, in 1953. He is a founding member of the so called group 93 and the magazine Baldus. His poetry has inspired an important debate, indeed, the last major debate of the last century about poetry.

In this interview with Mariano we would recall his entire poetic experience, from the debut with Hyperbaric Chamber (1983) until the last sestets published on magazine in 2003.

– In 1963, the group ‘63 gathers up near by Palermo, in order to discuss around the new avant-garde.

In 1969 Adriano Spatola published the essay Towards the total poetry.

How these two events have affected your poetic formation?

I thought, at first, with Greenberg, an art split into vanguard and falsehood. Later I have also been fascinated by the modern classicism. I think there is such oscillation in my work. But the echoes of the discussion of the Group ’63 have definitely affected upon my poetic education. What a great laboratory those discussions of poets, writers, critics. So many ideas to think about! For example, the idea that into the language is included not only the liberation, but also the alienation; a way of feeling that welcomes disharmony; a relationship with reality supported by a renewed sensory sensitivity; the commitment as something that should not give prior to the poetry, but it must be done with the same act of writing poetry; the contradictory: stay inside the literature by aiming at an out of the literature; taking away from the existent; the idea, of Umberto Eco, that the artist has started to be more and more, when he prepares to compose, a novice in the void… And Adriano Spatola, with its hypothesis of the total poetry, offered me the chance to reflect on a experimentation that went beyond encoded genres of the literature and which involved every expressive field, intersecting the writing, the voice, the image, the action. An art moved on orality as on the visual representation, on the body as on the mutual crossing of languages.

The ’70s mark the return of a poem less interested in linguistic experimentation, marked by a restoration of traditional modules. Fausto Curi defines this period with the name of “normalization”.

In the early 80’s – and precisely in 1983 – is published your first book, Hyperbaric Chamber. This book is a collection of poems in blank verse, short poems, prose and images. It seems something not indicated to enter in a hyperbaric chamber. It seems something completely at odds with that idea of “normalization”. What is your hyperbaric chamber?

I owe my debut to Adriano Spatola (who also designed the cover of the book) and to his editions of Tam Tam. The great season of the new avant-garde was over, and the definition of Curi of those years is correct. There was a return to order for poetry; the lyrical attitude of mythologizing the figure of the poet, to the detriment of the experimental practices. In all this, Adriano Spatola represented a point of resistance of the vanguard, not only in the lyrics but also in the production of autonomous typography objects. For my part, I felt no more authentic, not practicable, mimetic poetry and schemes of writing dominated by the metaphor.

The poetic-visual research of Hyperbaric Chamber collected texts made of a discontinuous, asymmetric emergence of fragments of speech. Verbal architectures in which isolated elements, lexemes, phrases, had a conceptual sense. An irregular succession of provisional units in which sometimes the linguistic material had a labyrinthine disposition. The graphic meanings not aspired to the transparency of communication, they wanted to be perceived for the material consistency of their sign. In addition to this displayed writing there were object-poems, visual poems, the attempt of an inter-code between “visual” and “verbal”. The book’s title drew the environment where is practiced the hyperbaric therapy, that creates a pressure greater than the atmospheric one. A rise of blood oxygenation to cure the air embolism. A press on the reader, but for a good purpose.

The magazine “Baldus” and the group ’93 make the coordinates of your poetry clear. Probably the group ’93 is the latest literary group of Italian literature. What your aims and, looking back, what are the greatest merit of the group ’93?

In the late eighties I share with other poets, and in particular with Biagio Cepollaro and Lello Voce, a hardship due to the postmodern cultural koinè, with the indifferent combination to everything with each other: the elimination of borders, distinctions, critical distance. We felt that our time was an après le deluge, and that could no longer be cultivate illusions about the revolutionary capabilities of the language, which had not produced (nor could do so in the future) upheavals in ideology. Hence the disillusionment, even to our own past, and the need for a common reflection on texts, the search for a sense, for a direction. These were the prerequisites for the emergence of the magazine “Baldus”.

With the seventh edition of “Milano-poetry”, in September 1989, was born the Group 93. There were a clear reference to the Group ‘63, but we also wanted to indicate the year of termination of our group. No aspiration to group together in a rigid form. A project aware of his precariousness, indifferent to the organicity and to the system. We wanted a place of interaction, not a poetic group. We spoke of “dialogicity of the heterogeneous.” The “postmodern critic” suggested by “Baldus” and shared by a part of the Group ‘93 was an oxymoronic formula: on the one hand it accepted the postmodern as an historical condition, such as the lack of the antithesis of the modern (including the one between vanguard and tradition); on the other hand it wanted to give to the pastiche (for Jameson the organic form of postmodernism, where contamination is uncritical and each element is similar to another) the character of the critical issues, of the “critics in action”, to quote a Proustian expression. A work on the margins, along a narrow ridge, to give even to the elements gathered in the assembly of the text a dialectic tension. A critical use of the contamination.

A literature not even more of second, but of umpteenth grade. It wanted to treat the postmodern as a reference to invest, to overcome, with a polyphonic reactivity given by fragments of the literature of the past and the thousand voices of the present. This means that is necessary to revive both the avant-garde and the tradition, in a new work of poetry. In the processing of those years there is, perhaps, a merit: the timely reading of the scenario. Although in few, we have tried to go in a new space.

Yellow fax is perhaps the crossroads of your poetic experience. The words coming out of the fax describe the world and – doing it – upset and overshadow the poet. It was 1993.

Do you think that today the social networks have upset and “gagged” the poetic voice, leading to completion the operation that had started your yellow fax?

The compositional concept was to show a continuous burst of messages of a fax in the stream of consciousness. It was difficult to distinguish, for the reader, the “voice” of the fax by the internal production of the poet. I wanted to call the speed and violence of the pressure of technology and the imaginary masses on the subject, that confuse him, compromise attempts to establish itself as a center. Referring to the super fast rhythm of Yellow fax, Renato Barilli – during a meeting of “Ricercare” at the Teatro Valli in Reggio Emilia – spoke of suitcases in the act of falling on each other on a moving walkway.

I had in mind, in writing, not only issues relating to multilingualism, to contamination, to the construction of my poetic language, but also an idea of the game in its mechanic meaning: a movable coupling, a space between two surfaces that allows the movement. Yellow fax wanted to establish itself as a space that avoids the blocking, the paralysis between the surface of the contemporary reality with its drifts, and the area given from the ability of opposition and responsiveness of the subject. In the best poetry of the following generation to the mine – I mean that one which is still trying to place themselves in a line of research – it seems that the textual strategies want to evoke the void of meaning and of the language. Perhaps a subject’s resistance is no longer possible. Perhaps the block occurred. Social networks, with the exhibition of our liquid life, affect especially the very young poets, pushing them to the effusivity and to the mythicization of the the poet.

Ônne ‘e terra (1994) proposes a highly literary use of dialect and a theorization of the “comedian”, as exaltation of the richness of linguistic possibilities. How important is the dialectal component in your linguistic experimentation?

It is very important. The dialect component means something like a return of the repressed, in the historical and anthropological field. However, the contact with the shards of a dialect (a loser “language”, assaulted from the Italian and from another more global language) has never had a sense of a nostalgic operation, a flow back toward an ancestral unrecoverable language, small homelands, haggard communities. Poetry cannot linger to reverberate issues that have no more basis in reality. The world – with a quote of Diderot – begins and ends without rest. The ” dialectal field ” attracted me as a phenomenon of ongoing transformation and metamorphosis. A place of friction in which the disappearance of the traditional communities is the point from which to move. A use of dialect is in all my texts, mixed with Italian, French and Spanish. With Onne e terra I wanted to write of Naples, to create a poem that is not “local”, but “of the place”. I said in a questionnaire proposed to me by the magazine “Diverse lingue” (year X, n. 14, 1995): “The need for a ‘whole dialectal expression continued to seem the only guarantee to cross my living places, but this way was complicated by the polyglot ingredients of my work already in progress. My dialectal research consists in having accepted the flânerie in those places, taking with them the disillusion related to the possibilities of establishing a new style than the existing; the need to equip, with different codes and languages, a linguistic tool not irenic; the cultural mediations necessary to not hide the contemporary babel of languages and not to grant special statutes of poetic value to the dialect. It also consists in having accepted to talk to the genius loci of Naples, letting his tongue, the Neapolitan, be the factor which gathers the other compositional factors. The sense of this flânerie dialogique, of crossing the maze-cities from lattice of his tongue, can perhaps be considered […] the core in relation to which, in this book, I chose the dialect.”

About the comedian field, in the text there is a carnivalesque thought. Not only because it evoke dice games, greasy poles, pranksters Kings: the eccentricity and the continuous mobility of the forms are two main characteristics of carnival. Dialogism and comedian obviously lead to Bachtin, whose reading was for me and my associates bent on attempting to lower the polyphony, the interdiscoursiveness – thought by the Russian theorist as exclusive of the novel – in the traditional monody of poetry. Onne ‘e terra, as a literary carnivalisque text, intends to overthrow the allegorical, the irreverent unveiling of a mask: that of Naples and its “Neapolitan”. The comedian peeps even in continuous changes of rhythm and intonation, and as a surprise with the linguistic possibilities. It seemed favored by the ability of the Neapolitan dialect of reviving, in a particular linguistic multiversum, different ages.

The re-writing is a practice dear at any experimentalism. In Pinocchio (moviole) your rewriting of Collodi results into a question about the role of poetry and of the poet himself, who is carried away by the flow of discourse and who“resigned” when we still have not reached the last page. It is 2000. The resignation of the poet may mark the end of a century, the declining curtain on the poetry?

Yeah, the hypertext of Pinocchio (moviole) … In the transformation of the Collodi’s text, in a brief piece in prose, the author splits himself: there is the “neocollodi on duty”, which leaves unfinished pieces and characters into the fray; there is an editor who cannot control the diegesis and he resigned, jumps down “from the book that sinks”.

The paradoxical situation, the question about who is writing, the act of resigning, may perhaps have a scope wider than revisitation of the Collodi’s opera. In presenting an anthology of young Italian poets, I said that they had made “the wrong step of the poetic existence (and resistance?)” The current society does not seem to know where to put the poetry. Society neglects it as use value, nor knows how to transform it into a commodity. I said that the best would be the self-defense of an exit strategy from the genre. I honestly do not know if poetry is come to an end with the “short century” and if the new century-millennium is going on towards other production of art and reality.

The impression, for now, is that the “poetic” should be confirmed as the emphasis of identity, combined with the trivialization of the form, or as a spectacle. For my part, I never really presented the resignation, continuing to take care of two collections of poetry (for editions of Bibliopolis and Oedipus). Especially in proposing authors of younger generations I have tried to trace a line of research, a poem macerated by doubt on the unity of the subject, addressed to his rift, the contradiction between “mean” and “not being able to say”. Not always I felt in tune with these texts, but I’ve given them an objective consensus. In my private I continue to write poems, particularly in the form of the sonnet. I allow myself the freedom of not having to think decisively if the rhythm is an illusion or not. I like to think, with Laforgue, to have “the infinite in the shipyard.” Or in the drawer, at least.

With Sparigli Marsigliesi (2002, then 2003), Amarellimerick (2002) and the sextuplets (published in the magazine in the same year) your poetic experience encounters and renews the traditional metrical schemes. Is this your phase of “normalization” or a new experimentation?

My visible poetic experience, the story of the publications, stops with those texts. In the first two, the situation is ludic. In both the work is on the comic language, that I had identified as a direction to follow already in the eighties (there is a trace in the journal “Altri termini”, 6-7-8, 1986-87). The calembour, the witz, the mot-valise, the autonomy of the signifier, metonymic chains, the materiality of the word, in the first text (in dialect and in Italian, and dedicated to the deck of Tarot cards) result in a dense verbal concentration, a game that refuses a geometric closure. The second one proposes, grafting the mot-valise, the metric structure of the limerick created by Edward Lear or rather some rhythmic variant, because that meter is not reproducible in Italian. In sextuplets is the creolization of Italian and Neapolitan. In any case, I was never interested in the contrast between free verse and new metric. In Onne e terra I had translated three sonnets of Gόngora; Fax giallo is composed of parts with the same number of verses. I’m with Derek Walcott, who uses open and closed forms. Eugenio Montale said that the problem of the open or closed forms is of little interest, because, in any case, there is no poetry without artifice. I esteemed, with Onne ‘e terra, to have reached 2.5 readers: I do not think, with the latest evidence, to have increased much the audience, to be passed by the fate of the “auteurs Dificiles” to that of the “liale”.

After more than twenty years by the group ’93, the season of poetic experiments now seems archived. Partial and “final” manuals on Italian poetry of the twentieth century have been written many and they will continue to be published.

Your poetic experience stops to 2003, coinciding with the beginning of the new millennium (we are aware of the fact that the clock of the centuries can’t be really punctual). Since then you’ve written three novels and a cauldron of thoughts (Le anatre di ghiaccio). Of this your production we will be happy to talk about it in another interview.

For the moment we like to close with one last question.

Doing a few sums with the century that has passed, the avant-garde that have occurred and normalization have taken over, don’t you feel like the last of the Italian poets of the twentieth century?

If we talk in a qualitative sense, perhaps I wouldn’t renounce to aspire, as a wagon wheel, to a moderate advance of position … In chronological sense, there is always a last of something. But I would think in a collective singularity.

Questions on the sidelines

The famous section 49 of Postkarten of Sanguineti (to prepare a poem takes a small true fact …) indicated the tools of the poet.

What are the tips of Mariano Bàino to prepare a poem?

Advice to others? No, thanks … The advice I always give to myself, but that does not concern the pre-writing, is to always remember a notation of Nietzsche, that wanted the art work, in every moment, “other” than what it is …

Which book would you recommend us to read?

Jurgis Baltrušaitis, The Mirror.

Bibliography of Mariano Baino

Poesia

- Camera iperbarica (Tam Tam, 1983)

- Fax Giallo (Nola, Il Laboratorio, 1993, poi Rapallo, Zona, 2001, con una nota di Gabriele Frasca)

- Ônne ‘e terra (Napoli, Pironti, 1994, poi Civitella in val di Chiana, Zona, 2003)

- Pinocchio (moviole) (Lecce, Manni, 2000)

- Sparigli marsigliesi (passar d’imago in mago fra i tarocchi)” (Nola, “Il Laboratorio”, 2002, poi Napoli, edizioni d’if, 2003)

- Amarellimerick (Salerno, Oèdipus, 2003)

Prosa

- Il mite e immite limite, in “Confini” (racconti di fine millennio), (Cava de’ Tirreni, Avagliano, 1998)

- Le anatre di ghiaccio (Napoli, l’ancora del mediterraneo, 2004)

- L’uomo avanzato (Firenze, Le Lettere, 2008)

- Dal rumore bianco (Napoli, Ad est dell’equatore, 2012)

- In (nessuna) Patagonia (Napoli, Ad est dell’equatore, 2014)

The ’70s mark the return of a poem less interested in linguistic experimentation, marked by a restoration of traditional modules. Fausto Curi defines this period with the name of “normalization”.

In the early 80’s – and precisely in 1983 – is published your first book, Hyperbaric Chamber. This book is a collection of poems in blank verse, short poems, prose and images. It seems something not indicated to enter in a hyperbaric chamber. It seems something completely at odds with that idea of “normalization”. What is your hyperbaric chamber?

I owe my debut to Adriano Spatola (who also designed the cover of the book) and to his editions of Tam Tam. The great season of the new avant-garde was over, and the definition of Curi of those years is correct. There was a return to order for poetry; the lyrical attitude of mythologizing the figure of the poet, to the detriment of the experimental practices. In all this, Adriano Spatola represented a point of resistance of the vanguard, not only in the lyrics but also in the production of autonomous typography objects. For my part, I felt no more authentic, not practicable, mimetic poetry and schemes of writing dominated by the metaphor.

The poetic-visual research of Hyperbaric Chamber collected texts made of a discontinuous, asymmetric emergence of fragments of speech. Verbal architectures in which isolated elements, lexemes, phrases, had a conceptual sense. An irregular succession of provisional units in which sometimes the linguistic material had a labyrinthine disposition. The graphic meanings not aspired to the transparency of communication, they wanted to be perceived for the material consistency of their sign. In addition to this displayed writing there were object-poems, visual poems, the attempt of an inter-code between “visual” and “verbal”. The book’s title drew the environment where is practiced the hyperbaric therapy, that creates a pressure greater than the atmospheric one. A rise of blood oxygenation to cure the air embolism. A press on the reader, but for a good purpose.

The magazine “Baldus” and the group ’93 make the coordinates of your poetry clear. Probably the group ’93 is the latest literary group of Italian literature. What your aims and, looking back, what are the greatest merit of the group ’93?

In the late eighties I share with other poets, and in particular with Biagio Cepollaro and Lello Voce, a hardship due to the postmodern cultural koinè, with the indifferent combination to everything with each other: the elimination of borders, distinctions, critical distance. We felt that our time was an après le deluge, and that could no longer be cultivate illusions about the revolutionary capabilities of the language, which had not produced (nor could do so in the future) upheavals in ideology. Hence the disillusionment, even to our own past, and the need for a common reflection on texts, the search for a sense, for a direction. These were the prerequisites for the emergence of the magazine “Baldus”.

With the seventh edition of “Milano-poetry”, in September 1989, was born the Group 93. There were a clear reference to the Group ‘63, but we also wanted to indicate the year of termination of our group. No aspiration to group together in a rigid form. A project aware of his precariousness, indifferent to the organicity and to the system. We wanted a place of interaction, not a poetic group. We spoke of “dialogicity of the heterogeneous.” The “postmodern critic” suggested by “Baldus” and shared by a part of the Group ‘93 was an oxymoronic formula: on the one hand it accepted the postmodern as an historical condition, such as the lack of the antithesis of the modern (including the one between vanguard and tradition); on the other hand it wanted to give to the pastiche (for Jameson the organic form of postmodernism, where contamination is uncritical and each element is similar to another) the character of the critical issues, of the “critics in action”, to quote a Proustian expression. A work on the margins, along a narrow ridge, to give even to the elements gathered in the assembly of the text a dialectic tension. A critical use of the contamination.

A literature not even more of second, but of umpteenth grade. It wanted to treat the postmodern as a reference to invest, to overcome, with a polyphonic reactivity given by fragments of the literature of the past and the thousand voices of the present. This means that is necessary to revive both the avant-garde and the tradition, in a new work of poetry. In the processing of those years there is, perhaps, a merit: the timely reading of the scenario. Although in few, we have tried to go in a new space.

Yellow fax is perhaps the crossroads of your poetic experience. The words coming out of the fax describe the world and – doing it – upset and overshadow the poet. It was 1993.

Do you think that today the social networks have upset and “gagged” the poetic voice, leading to completion the operation that had started your yellow fax?

The compositional concept was to show a continuous burst of messages of a fax in the stream of consciousness. It was difficult to distinguish, for the reader, the “voice” of the fax by the internal production of the poet. I wanted to call the speed and violence of the pressure of technology and the imaginary masses on the subject, that confuse him, compromise attempts to establish itself as a center. Referring to the super fast rhythm of Yellow fax, Renato Barilli – during a meeting of “Ricercare” at the Teatro Valli in Reggio Emilia – spoke of suitcases in the act of falling on each other on a moving walkway.

I had in mind, in writing, not only issues relating to multilingualism, to contamination, to the construction of my poetic language, but also an idea of the game in its mechanic meaning: a movable coupling, a space between two surfaces that allows the movement. Yellow fax wanted to establish itself as a space that avoids the blocking, the paralysis between the surface of the contemporary reality with its drifts, and the area given from the ability of opposition and responsiveness of the subject. In the best poetry of the following generation to the mine – I mean that one which is still trying to place themselves in a line of research – it seems that the textual strategies want to evoke the void of meaning and of the language. Perhaps a subject’s resistance is no longer possible. Perhaps the block occurred. Social networks, with the exhibition of our liquid life, affect especially the very young poets, pushing them to the effusivity and to the mythicization of the the poet.

Ônne ‘e terra (1994) proposes a highly literary use of dialect and a theorization of the “comedian”, as exaltation of the richness of linguistic possibilities. How important is the dialectal component in your linguistic experimentation?

It is very important. The dialect component means something like a return of the repressed, in the historical and anthropological field. However, the contact with the shards of a dialect (a loser “language”, assaulted from the Italian and from another more global language) has never had a sense of a nostalgic operation, a flow back toward an ancestral unrecoverable language, small homelands, haggard communities. Poetry cannot linger to reverberate issues that have no more basis in reality. The world – with a quote of Diderot – begins and ends without rest. The ” dialectal field ” attracted me as a phenomenon of ongoing transformation and metamorphosis. A place of friction in which the disappearance of the traditional communities is the point from which to move. A use of dialect is in all my texts, mixed with Italian, French and Spanish. With Onne e terra I wanted to write of Naples, to create a poem that is not “local”, but “of the place”. I said in a questionnaire proposed to me by the magazine “Diverse lingue” (year X, n. 14, 1995): “The need for a ‘whole dialectal expression continued to seem the only guarantee to cross my living places, but this way was complicated by the polyglot ingredients of my work already in progress. My dialectal research consists in having accepted the flânerie in those places, taking with them the disillusion related to the possibilities of establishing a new style than the existing; the need to equip, with different codes and languages, a linguistic tool not irenic; the cultural mediations necessary to not hide the contemporary babel of languages and not to grant special statutes of poetic value to the dialect. It also consists in having accepted to talk to the genius loci of Naples, letting his tongue, the Neapolitan, be the factor which gathers the other compositional factors. The sense of this flânerie dialogique, of crossing the maze-cities from lattice of his tongue, can perhaps be considered […] the core in relation to which, in this book, I chose the dialect.”

About the comedian field, in the text there is a carnivalesque thought. Not only because it evoke dice games, greasy poles, pranksters Kings: the eccentricity and the continuous mobility of the forms are two main characteristics of carnival. Dialogism and comedian obviously lead to Bachtin, whose reading was for me and my associates bent on attempting to lower the polyphony, the interdiscoursiveness – thought by the Russian theorist as exclusive of the novel – in the traditional monody of poetry. Onne ‘e terra, as a literary carnivalisque text, intends to overthrow the allegorical, the irreverent unveiling of a mask: that of Naples and its “Neapolitan”. The comedian peeps even in continuous changes of rhythm and intonation, and as a surprise with the linguistic possibilities. It seemed favored by the ability of the Neapolitan dialect of reviving, in a particular linguistic multiversum, different ages.

The re-writing is a practice dear at any experimentalism. In Pinocchio (moviole) your rewriting of Collodi results into a question about the role of poetry and of the poet himself, who is carried away by the flow of discourse and who“resigned” when we still have not reached the last page. It is 2000. The resignation of the poet may mark the end of a century, the declining curtain on the poetry?

Yeah, the hypertext of Pinocchio (moviole) … In the transformation of the Collodi’s text, in a brief piece in prose, the author splits himself: there is the “neocollodi on duty”, which leaves unfinished pieces and characters into the fray; there is an editor who cannot control the diegesis and he resigned, jumps down “from the book that sinks”.

The paradoxical situation, the question about who is writing, the act of resigning, may perhaps have a scope wider than revisitation of the Collodi’s opera. In presenting an anthology of young Italian poets, I said that they had made “the wrong step of the poetic existence (and resistance?)” The current society does not seem to know where to put the poetry. Society neglects it as use value, nor knows how to transform it into a commodity. I said that the best would be the self-defense of an exit strategy from the genre. I honestly do not know if poetry is come to an end with the “short century” and if the new century-millennium is going on towards other production of art and reality.

The impression, for now, is that the “poetic” should be confirmed as the emphasis of identity, combined with the trivialization of the form, or as a spectacle. For my part, I never really presented the resignation, continuing to take care of two collections of poetry (for editions of Bibliopolis and Oedipus). Especially in proposing authors of younger generations I have tried to trace a line of research, a poem macerated by doubt on the unity of the subject, addressed to his rift, the contradiction between “mean” and “not being able to say”. Not always I felt in tune with these texts, but I’ve given them an objective consensus. In my private I continue to write poems, particularly in the form of the sonnet. I allow myself the freedom of not having to think decisively if the rhythm is an illusion or not. I like to think, with Laforgue, to have “the infinite in the shipyard.” Or in the drawer, at least.

With Sparigli Marsigliesi (2002, then 2003), Amarellimerick (2002) and the sextuplets (published in the magazine in the same year) your poetic experience encounters and renews the traditional metrical schemes. Is this your phase of “normalization” or a new experimentation?

My visible poetic experience, the story of the publications, stops with those texts. In the first two, the situation is ludic. In both the work is on the comic language, that I had identified as a direction to follow already in the eighties (there is a trace in the journal “Altri termini”, 6-7-8, 1986-87). The calembour, the witz, the mot-valise, the autonomy of the signifier, metonymic chains, the materiality of the word, in the first text (in dialect and in Italian, and dedicated to the deck of Tarot cards) result in a dense verbal concentration, a game that refuses a geometric closure. The second one proposes, grafting the mot-valise, the metric structure of the limerick created by Edward Lear or rather some rhythmic variant, because that meter is not reproducible in Italian. In sextuplets is the creolization of Italian and Neapolitan. In any case, I was never interested in the contrast between free verse and new metric. In Onne e terra I had translated three sonnets of Gόngora; Fax giallo is composed of parts with the same number of verses. I’m with Derek Walcott, who uses open and closed forms. Eugenio Montale said that the problem of the open or closed forms is of little interest, because, in any case, there is no poetry without artifice. I esteemed, with Onne ‘e terra, to have reached 2.5 readers: I do not think, with the latest evidence, to have increased much the audience, to be passed by the fate of the “auteurs Dificiles” to that of the “liale”.

After more than twenty years by the group ’93, the season of poetic experiments now seems archived. Partial and “final” manuals on Italian poetry of the twentieth century have been written many and they will continue to be published.

Your poetic experience stops to 2003, coinciding with the beginning of the new millennium (we are aware of the fact that the clock of the centuries can’t be really punctual). Since then you’ve written three novels and a cauldron of thoughts (Le anatre di ghiaccio). Of this your production we will be happy to talk about it in another interview.

For the moment we like to close with one last question.

Doing a few sums with the century that has passed, the avant-garde that have occurred and normalization have taken over, don’t you feel like the last of the Italian poets of the twentieth century?

If we talk in a qualitative sense, perhaps I wouldn’t renounce to aspire, as a wagon wheel, to a moderate advance of position … In chronological sense, there is always a last of something. But I would think in a collective singularity.

Questions on the sidelines

The famous section 49 of Postkarten of Sanguineti (to prepare a poem takes a small true fact …) indicated the tools of the poet.

What are the tips of Mariano Bàino to prepare a poem?

Advice to others? No, thanks … The advice I always give to myself, but that does not concern the pre-writing, is to always remember a notation of Nietzsche, that wanted the art work, in every moment, “other” than what it is …

Which book would you recommend us to read?

Jurgis Baltrušaitis, The Mirror.

Bibliography of Mariano Baino

Poesia

- Camera iperbarica (Tam Tam, 1983)

- Fax Giallo (Nola, Il Laboratorio, 1993, poi Rapallo, Zona, 2001, con una nota di Gabriele Frasca)

- Ônne ‘e terra (Napoli, Pironti, 1994, poi Civitella in val di Chiana, Zona, 2003)

- Pinocchio (moviole) (Lecce, Manni, 2000)

- Sparigli marsigliesi (passar d’imago in mago fra i tarocchi)” (Nola, “Il Laboratorio”, 2002, poi Napoli, edizioni d’if, 2003)

- Amarellimerick (Salerno, Oèdipus, 2003)

Prosa

- Il mite e immite limite, in “Confini” (racconti di fine millennio), (Cava de’ Tirreni, Avagliano, 1998)

- Le anatre di ghiaccio (Napoli, l’ancora del mediterraneo, 2004)

- L’uomo avanzato (Firenze, Le Lettere, 2008)

- Dal rumore bianco (Napoli, Ad est dell’equatore, 2012)

- In (nessuna) Patagonia (Napoli, Ad est dell’equatore, 2014)

Veramente interessante il percorso metamorfico di Mariano Baino. Il suo linguaggio poetico rappresenta questa caleidoscopica ricerca di identità: dubbio, contraddizione, sperimentazione, dialogicità, contaminazione sono i termini più significativi del suo iter di organica discontinuità.